OFFICES ON THE BEACH

Billionaires bankroll Class A office space near their homes

Read the original article here.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, when developers cleared away vegetation and alligators from a sandbar just off the coast of Miami, Miami Beach has been a retreat for the wealthy wishing to escape cold winters.

But now the wealthy don’t want to just play in Miami Beach; they want to work there, too. More wealthy executives, including those who arrived during the Covid-19 pandemic, are bankrolling buildings and leasing office space close to their sprawling mansions and luxury condominiums. It’s a burgeoning trend that could help change the perception of Miami Beach as a place just for fun and sun.

The city is poised to welcome its first top-of-the-line Class A office projects in years as officials are eager to fast-track office development to diversify the municipality’s economy beyond hospitality.

Stephen Rutchik, executive managing director of office services at Colliers (NYSE: CIGI), said the demand for Class A office space is driven by principal decision-makers and their employees who live in Miami Beach and want to avoid commuting on South Florida’s congested roads.

“Living and having an office on Miami Beach is a quality-of-life decision,” he said.

There are 4.9 million square feet of office space in greater Miami Beach – which includes Surfside, Bal Harbour, Bay Harbor Islands and Sunny Isles Beach – according to Colliers’ 2021 fourth quarter office market report. However, only 1.3 million square feet of that are the Class A spaces sought by companies hoping to encourage remote workers to spend more time in the office.

By comparison, downtown Miami has 5.1 million square feet of Class A space available, and the Brickell Financial District has 4.8 million square feet, the Colliers report stated.

Lyle Stern, co-founder of Miami Beach-based commercial brokerage Koniver Stern Group, said billionaires, technology and investment companies have been opening offices in Miami Beach for years, but that pace has quickened during the pandemic. However, hardly any Class A office space has been built since the early 2000s, he said.

“The vast majority of [wealthy] folks who moved down here during the pandemic want an office here; they just cannot find office space,” Stern said. “We are not just talking about someone sitting at home with a computer, but someone who has six, seven, eight, nine, 10 analysts working for him, as well.”

Office surge

Despite the rise of the work-from-home trend, the commercial office sector is finally showing signs of recovery.

Nationwide, asking rental rates increased 1.4% year-over-year, according to a December 2021 report from CommercialEdge, a Santa Barbara, California-based commercial real estate data platform. In the first 11 months of 2021, $68.8 billion worth of office transactions took place, a figure that exceeded 2020’s sales volume by 11%.

Mirroring national trends, the South Florida office market has been strong, especially in Miami-Dade County, as local businesses seek to expand and companies from other parts of the U.S. relocate to Florida for its warm weather and tax benefits.

According to Colliers, fourth quarter vacancies in Miami-Dade were 11% and asking rents averaged $44.72 a square foot. Nationwide, vacancies averaged 15.2%, with rents $38.62 a square foot, according to CommercialEdge.

In Miami Beach, average office rents were $53.73 a square foot in the fourth quarter, a 4.2% hike from the previous quarter, Colliers reported.

That isn’t as high as submarkets such as the Wynwood Arts District and Miami Design District ($59.38) or Brickell ($63.95). But Miami Beach rates do surpass other areas in Miami-Dade, including the Biscayne corridor ($38.11), Coral Gables ($45.16), Aventura ($48.90) and Miami International Airport ($35.87).

In terms of available space, Miami Beach has a vacancy rate of 8.4%. That’s lower than the vacancy rates of Wynwood (19.8%), Brickell (11.9%), and downtown Miami (24.4%).

Office leasing activity in South Beach has ramped up since the third quarter of last year, Colliers’ Rutchik said. “That’s when you see leases executed and the momentum picking up.”

Most of the businesses seeking office space in Miami Beach are related to finance, including private equity firms, hedge funds and family offices – a boutique operation that focuses on investing capital from a single household.

With vacancies at a considerable low in the city, some billionaires have sought to build offices of their own.

Barry Sternlicht, president and CEO of Starwood Capital Group, an investment firm overseeing $100 billion in assets, moved his company’s headquarters out of Lincoln Place at 1601 Washington Ave. after completing a new 144,430-square-foot building at 2340 Collins Ave. And energy investor and Miami Beach resident Wayne Boich is constructing a 15,997-square-foot office at 1910 Alton Road that will include a penthouse for him on the fifth floor.

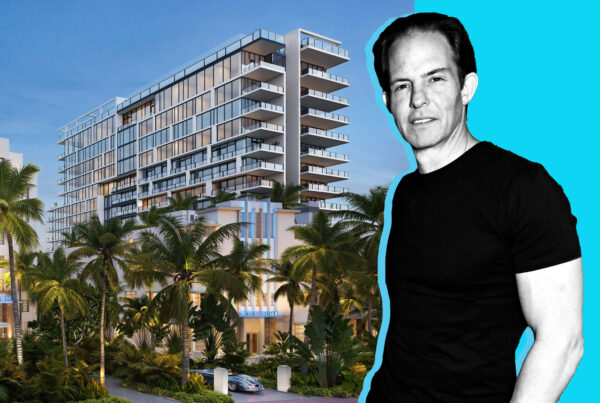

Colliers’ Rutchik said he is negotiating per-square-footage rents in the low to mid-$100s for Eighteen Sunset, a mixed-use office project at 1733 Purdy Ave., which is slated for completion in 2023. The project is being developed by Marc Rowan, CEO of New York-based Apollo Global Management (NYSE: APO), and Bradley Colmer, managing partner of Miami Beach-based Deco Capital Group.

Colmer said he originally planned to build a residential building in Sunset Harbour. But he opted to build a Class A office project when he noted older office buildings in Miami Beach were snaring premium rents “for product that you would typically call Class B,” leaving money on the table for any developer willing to offer more amenities.

“We thought there was an opportunity there,” he said.

Diversifying the economy

The Miami Beach City Commission already increased the height limits of office buildings to 75 feet on Terminal Island, western segments of Alton Road, and within the Sunset Harbour Overlay district. On Collins Avenue between Sixth and 16th streets, where height for new construction is maxed out at 50 feet, an urban plan designed by architect Bernard Zyscovich would include 75-foot-tall Class A office structures. The city also issued a request for proposals for developers interested in turning three city parking lots and the municipality’s 17th Street parking garage into Class A offices.

Rickelle Williams, Miami Beach’s director of economic development, said encouraging more Class A office development is part of a strategy to attract businesses in industries that employ a high-wage workforce. That includes technology and financial services firms, as well as companies willing to relocate corporate or regional headquarters, or expand existing offices. That mostly leaves out hospitality businesses, known for paying lower wages.

The city’s strategy includes expediting the permitting process for office projects and giving up to $60,000 a year for the next four years to companies with more than 10 full-time jobs that pay more than $69,385 a year. (The exact amount awarded depends on the number of jobs.)

Williams said four companies – including Wix.com, a Tel Aviv, Israel-based company that employs about 300 people at The Lincoln, at 1691 Michigan Ave. – have already used the financial job incentive program.

The drive to diversify the economy coincides with a desire by many city voters to curtail rowdy party crowds. In November, 56.5% of voters passed a non-binding referendum to roll back last call for alcohol to 2 a.m. from 5 a.m. This would be a blow to hospitality businesses in South Florida’s top tourist destination.

Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber wants to reduce the number of bars in South Beach’s Collins Avenue and Ocean Drive, arguing that they are preventing the city from diversifying the economy beyond low-paying hospitality jobs.

“The reason why I want to get rid of most of these all-night places is they stop other things from coming in,” he told the Business Journal.

Looking ahead

Still, a question remains: When offices in the pipeline are completed on Miami Beach in a few years, will anyone still want to move in?

At the height of the dot-com boom in the late 1990s, several new offices broke ground or were constructed. But by 2000, the early internet companies collapsed and office landlords had trouble finding tenants.

Scott Robins, founder of the Robins Cos., codeveloped three Class A offices in Miami Beach in the early 2000s: Lincoln Place, The Lincoln and 555 Washington. They were completed after the dot-com bubble burst and much of that demand evaporated, he said, adding that it took a few years before he could fill the offices with “quality tenants.”

But Robins thinks the office boom will stick this time around, thanks to the continued migration of companies and people to the Sunshine State.

“The fact that you can work remotely has been accelerated by the Covid pandemic, plus the increase in taxes all over the country and Florida being the least-taxed state in the nation [makes] South Florida very appealing,” he said.

Plus, “the quality of life on Miami Beach is just better,” Robins said.

Deco Capital Group’s Colmer said the region is much different than it was two decades ago.

“We have more wealth, more high-net-worth individuals, and more ability for people to operate in multiple places,” he said. “And I think all of that is contributing to the desire, among decision-makers, to be in South Florida.”